Żary 2025-05-18

Railway station Żary.

Construction of the railway in Prussia.

In the 19th century, the organization of work in Prussia was strongly associated with the economic and social changes resulting from the industrial revolution, agrarian reforms and the development of the Prussian state as a strong bureaucratic monarchy. At the beginning of the 19th century (1807–1816), the Stein-Hardenberg reforms were introduced, which abolished serfdom and allowed peasants to acquire land for themselves. But the peasants did not have the financial resources, so banks came to the rescue, granting loans at high interest (usury). As a result, a significant number of landless rural workers were created, who were called farmhands. Only a small class of independent peasants, farmers, emerged. Many peasants and rural workers took seasonal work on landed estates, often on a contract basis. From the mid-19th century, especially after 1850, the development of industry intensified; mainly mining, metallurgy and the textile industry. Large industrial plants were established, in which work was organized in a hierarchical manner, with division into management and workers. Industrial plants had strict work regulations, there were penalties for lateness, and the workday lasted 12-14 hours. The rural poor moved to cities in search of work, which encouraged the emergence of a proletariat class. As a result, an excellent ground was created for the development of communism. Let us also remember that in Prussia there was no attachment to religion, because since the Reformation, confusion had been created in the minds of the lower social classes. Workers often worked in difficult conditions, without social security. In factories, women and children worked equally with men. In the first half of the 19th century, workers were deprived of the right to organize, strike or negotiate working conditions. Prussian authorities feared the radicalization of the working class, so they used various forms of supervision and repression.

The Prussian monarchy was an absolute and bureaucratic monarchy. Work in the administration was highly hierarchical, based on loyalty to the state and official discipline. Compulsory schooling was introduced and vocational schools were developed, which was to prepare young people for work in industry or administration. It was not until the end of the 19th century that the social situation of workers began to improve. Social insurance was introduced: sickness insurance (1883), accident insurance (1884), retirement insurance (1889). This was to counteract the radicalization of the labor movement and strengthen loyalty to the state, or rather the administration. Let us remember that social insurance was only applicable to workers working on the basis of a written contract, which was concluded only after a minimum of 5 years of work.

The work of Prussian workers on construction sites in the 19th century was hard, poorly paid and without social protection, but also crucial for the development of urbanization and infrastructure in Prussia. Construction work was usually seasonal, performed from spring to autumn. In winter, there was often no employment. The work included the construction of houses, factories, bridges, roads, railways and canals. The development of railways was particularly intensive, dating from the 1840s. Most of the work was done by hand, with the help of shovels, pickaxes and hammers. Wheelbarrows were mainly used for transport. Construction machines such as cranes, concrete mixers, and saws were rare. Workers were organized into work groups (brigades) supervised by a master (foreman). Many workers had no vocational education and this was a workforce from the poorest social classes, often from rural areas or from the Moscow and Austrian partitions. Contracts were oral or short-term, and payments often depended on the completion of the task. Construction workers’ earnings were low and employment was uncertain. There was no assistance in the event of illness or accident. Work lasted 12-14 hours a day, from dawn to dusk, with only one day off, Sunday. Workers often lived in barracks, without toilets or clean water. Diseases often developed, often contagious. There were no health and safety regulations, no gloves, no helmets, the scaffolding was temporary, and accidents were very common. The injured and sick often lost the opportunity to continue working and did not receive any benefits. Construction workers were a low social class, deprived of respect and even the opportunity to practice their faith. Workers were considered unskilled. It was not until the end of the 19th century that trade unions and craft associations began to be formed, which fought for the improvement of working conditions.

Testimony of a Prussian worker from 1880 – “We get up before dawn and eat bread and drink black coffee. We walk to the construction site, over two kilometers. Work begins as soon as you can see something. Stone by stone, brick by brick. Your hands refuse to obey. There are no breaks in work. Talking to the foreman is punishable by punishment or dismissal. There were financial penalties for misdemeanors. When there were delays in work, you had to go to work on Sundays. It was the hardest to work in the rain, because there was no downtime.”

Compared to England and France, Prussia was worse. The day was longer; 12-14. Social security was not introduced until the end of the 19th century. There were no trade unions, and the concept of a strike did not exist. Until the end of the 19th century, Germans did not understand that a skilled worker was valuable.

Railway lines in Prussia were built quickly and in large numbers, but of poor quality. Iron rails, 12 m long, were often used. Wooden pine and spruce sleepers were used, which were not impregnated. No metal sleepers were provided under the rails and the rails were attached only with nails. Gravel was used as a sleeper, and very rarely crushed stone, of an appropriate grade. The lines were marked out in long straight sections, from city to city. The lines had to be approved personally by the king, because he was a great supporter of them. It was not until the end of the 19th century that local communities joined in the construction of the lines, building very winding lines, but connecting workplaces, factories and warehouses in a given area. They were also built at a low cost and often required renovation. The advantage of these lines was the same European gauge, which allowed any wagon to enter.

Żary Railway Station.

Geographic coordinates: 51.634N 15.137E. Elevation 156 m. Address ulica Długosza 1, 68-200 Żary.

City of Żary.

Żary is a city in Poland in the Lubuskie Voivodeship, Żary County. In 2021, the city’s population was 36,004 inhabitants. The city’s area is 33.49 km2. The average elevation is 160 m. The city lies on the Szprotawa Plain, between two tributaries of the Odra: the Bober and the Lubsza, which has its sources nearby. The city has spread to the north-east, because there are flat areas here. To the south-west is the Żarskie Upland, and the highest is 227 m above sea level. The terrain was shaped by the third, last glaciation. The original name of the town was the Lusatian name Žarow, which comes from the burning of forests in the process of settlement. In May 2010, the town celebrated the 750th anniversary of its location. The history of Żary (Sorau in Germanic) dates back to the Middle Ages. The town played an important administrative, economic and cultural role in the region of the historical Lower Lusatia. The first mention of the settlement of Żary dates back to 1007, and was cited in the subject of Bolesław the Brave’s battles with the Germans over Lusatia. In 1207, the settlement was surrounded by cold ramparts and a wooden palisade. Żary received city rights in around 1260, thanks to Duke Henry III of Głogów. The settlement was established on one of the salt tracts, in the area of the Zielona Góra Forest. Tar-making and charcoal production developed here. The town often changed national affiliation. From the 13th to the 15th century, Żary belonged to the Piast princes, later coming under Czech, Hungarian and then Habsburg rule. In the 16th century, the inhabitants converted to Protestantism and the city became the centre of the Reformation and religious turmoil. From the 17th to the 18th century, Żary was the seat of the powerful Promnitz family. During their rule, a baroque palace was built, now a ruin. The city was destroyed by fires, plagues and foreign armies. In 1815, Żary, together with the entire Lower Lusatia, became part of the Kingdom of Prussia. With the industrial revolution, Żary became an important centre of the textile, machine and furniture industries. The railway connecting the city to Żary contributed to the development of industry. The city’s infrastructure was developed.

Unfortunately, the Germans once again started the second great world war. As a result, the Germans lost a lot. On April 11, 1944, after an Allied air raid, part of the city lay in ruins and burned down. On February 16, 1945, the Soviet army entered the city. The city’s population decreased from 26,000 (1940) to 4,000 inhabitants (spring 1945). As a result of the Potsdam Conference, in 1945, the Polish border moved significantly west. Żary was settled by the Polish population, which Stalin had expelled from the Polish Borderlands. A significant percentage of these were people from the regions of Lviv, Tarnopol and Stanisławów. The Germans were resettled west. In September 1945, there were already about 1,500 Poles in Żary, and in December 1946, there were already 27,000 Polish settlers. A military and public hospital was set up in the former psychiatric hospital. During the PRL (Communist Poland) times, Żary became an industrial city, with textile, food and electromechanical plants operating. In 1972, the settlement of Kunice was incorporated into Żary, as a result of which the city’s population increased by 11%.

After 1989, as a result of socio-economic changes, the city’s economy went through a difficult period of transformation. A period in which the communists transformed into businessmen and seized state property. There was no vetting and decommunization, and as a result, successive generations of communists, freemasons and Volksdeutsche rule in the Republic of Poland.

Currently, Żary is one of the largest and well-developed cities in the Lubuskie Province. Żary is the largest city in the Lubuskie Region. The city of Żary is called the Polish Heart of Lusatia. Despite the destruction of war, many Prussian monuments have been preserved in the city. However, the greatest intellectual value of the city is the cultivation of customs from the Polish Borderlands by its inhabitants. The most important monuments: Castle complex, from the 14th–18th centuries: Dewinów-Bibersteinów Castle is a Gothic castle built on the initiative of Albrecht Dziewin, in the second half of the 13th century, rebuilt in the period 1540–1549 by the Bibersteins and acquired a Renaissance character. Promnitzów Palace, Baroque, designed by the Swiss architect Giovanni Simonetti; it was built in the period 1710–1728 as a monumental, four-winged complex with a courtyard in the middle, adjacent to the castle. Railway station.

Historic industrial plants in Żary: Johann Gottfried Frenzel Factory (founded in 1830). One of the oldest textile factories in Żary, known for producing fabrics exported to the USA. It was the first factory in the region to use locomobiles to power machinery. After the war, transformed into the Decorative Fabrics Plant “Dekora”. Theodor Kosak Mechanische Weberei – Sorau factory, a pre-war textile factory, which after 1945, was taken over by the state and transformed into the Żary Clothing Industry Plants. Sorauer Porzellanfabrik factory (1888–1945). A porcelain factory producing tableware, known for exporting its products to Europe and the USA. The Wool Industry Plant “Wełna”. The plants, created by the merger of the plants in Żary and Żagań in 1973, produced wool fabrics. Focke-Wulf factory, which produced aircraft parts during World War II and was a branch of the German aircraft factory Focke-Wulf.

Current factories in Żary: Kronopol Sp. z o.o. (Swiss Krono Group). Manufacturer of MDF, OSB and laminated panels. One of the largest employers in the region, employing over 1,000 people. In 1977, the factory was significantly expanded. Valmet Automotive Sp. z o.o. Manufacturer of roofing and kinematic systems for the automotive industry. The plant is currently being expanded and plans are to increase employment to over 1,000 people by 2027. Qemetica Vitrosilicon factory (formerly CIECH Vitrosilicon). Manufacturer of glass and sodium silicates, employing over 100 people. Smulders Projects Poland Sp. z o.o. Manufacturer of steel structures, operating in the renewable energy sector. Saint-Gobain Sekurit Transport Factory. Manufacturer of glass and system solutions for commercial vehicles, such as buses and trucks. HART-SM Factory. Manufacturer of tempered glass, with modern production departments, with a total area of approximately 50,000 m2. DADA Industrial Services Sp. z o.o. Factory specializing in industrial services, with headquarters at ul. Podchorążych 118. METAL TOM Sp. z o.o. Factory dealing with metal processing, located at ul. Słowackiego 4.

Railway in the city of Żary.

Interestingly, the station in Żary, in a city with a population of 36,000, is smaller than the station in Żagań, where the city’s population is 25,660. The distance between the cities is only 15 km.

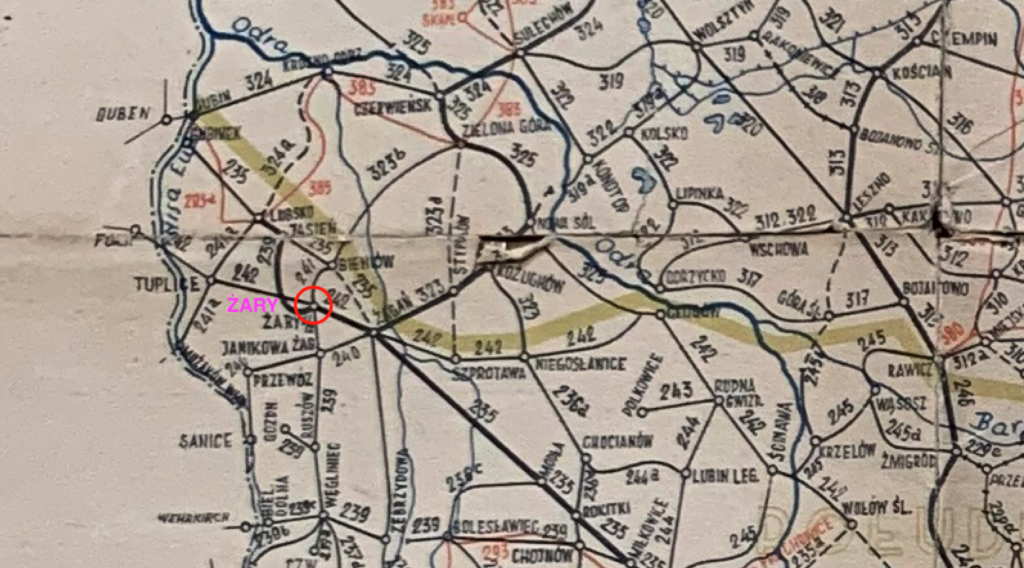

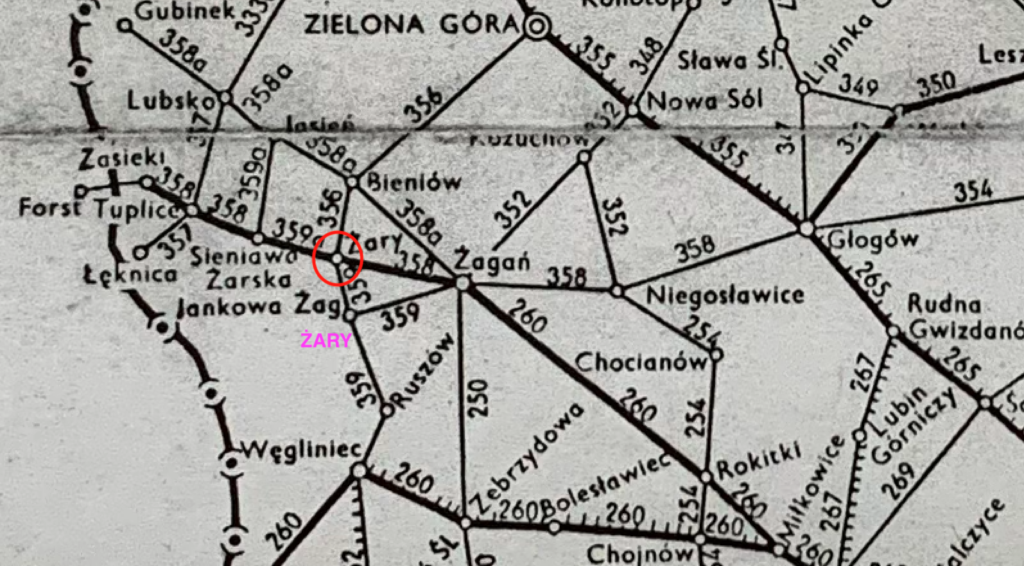

In 1846, Żary was included in the first railway line Wrocław – Berlin. It was the oldest railway line in the Żary region. The railway reached here thanks to the expansion of the Niederlausitzer Eisenbahn (Lower Lusatian Railway). Soon the city became an important railway junction. Railway sidings were built to textile factories and sawmills, among others.

In 1945, the railway infrastructure was significantly destroyed. The Soviets took a lot of railway equipment to Moscow. With difficulty, Polish railway workers started the movement of freight and passenger trains. During the times of the Polish People’s Republic, regional traffic developed: Zielona Góra, Wrocław, Legnica. There were also long-distance trains to Poznań, Warsaw and Katowice. Until 1993, there were many Soviet echelons due to the military units stationed in the area. Żary station was a transshipment point for many industrial plants. At Żary station there was a fan-shaped locomotive shed, 8-stands (western side of the station), which was called a wagon shed here. Over the years, various series of locomotives were stationed here, including: steam locomotives of the Ty2 series, and later diesel ST43, ST44, SU45 and SU46. There was also a water tower in the facility. There was a turntable, coal entanglements, warehouses and five signal boxes. The railway turntable (eastern side of the station) was entered on the list of historical monuments after registration number L-865/A on September 14, 2021. There was a locomotive shed with three stands here, and currently there is a car repair shop.

After 1989, there was a decline in freight and passenger transport. Many local lines and passenger connections were closed, for example to Lubsko, Gubin or Brody. Since 2015, there has been a gradual increase in rail transport. Renovation of some railway lines and infrastructure has begun. Passenger trains have returned to the routes. Regional trains serve the following directions: Zielona Góra, Żagań, Wrocław, Legnica, Forst (RFN).

The station in Żagań was built in 1846. The station is located between the tracks, i.e. it is an island station. Interestingly, compared to other island stations, there is no possibility of reaching the station building by car and there is no station square. Access to the station is provided by a tunnel leading from Długosza Street, from the northern side of the station, which leads directly to the station hall. The station building consists of two connected buildings, which are rectangular in their base. The station has two storeys and a partial basement. In addition, there are three single-storey extensions. The total length of the station is 84 m and the width is 20 m. The station is covered with a hipped roof with a slight slope. The building has few decorative details. There are cornices and window frames. The windows in the upper part have small arches. On the city side, in the eastern part, the windows have a semicircular ending. In one of the extensions there were toilets, which are currently located inside the station, access from the main station hall. In 2015, the station building was renovated. The renovation work did not include the shelters on the platforms and the entrance portal from the city side. The old toilets were demolished. The platform shelters were renovated in 2017. Only the main entrance to the tunnel from the city side, with a bas-relief in the form of a winged wheel, a railway sign, remained without renovation.

Currently, there are 4 platforms and 5 platform edges at the station. There are metal and wooden shelters on the platforms. The surface of the platforms is paved or asphalt. In addition to the main tunnel (Dlugosza Street – station hall), Platform 1 and Platform 2, on the southern side of the station, are connected by a separate tunnel. Platform 1, single-edge, is 180 m long and has a roof from the length of 40 m. Platform 2, double-edge, is 247 m long and has a roof from the length of 83 m. Platform 3, single-edge, is 207 m long and has a roof from the length of 43 m. Platform 4 is an island, but single-edge. It is 207 m long, has no roof, because it is a narrow platform, and its surface is made of concrete slabs.

The western part of the station is the freight part. The total length of the station is 1,650 m. There are four signal boxes at the station; “Ża”, “Ża1”, “Ża2”, “Ża3” (inactive), “Ża4”. There are shape semaphores at the station. The inactive locomotive shed in the eastern part of the station had three stands. Currently, there is a car repair shop here. In the western part of the station, there is also an impressive, inactive WAGON SHOP building, which also houses a water tower and had 8 stands. The building is built of red brick and is multi-body. The building is currently a permanent ruin and is located at Przeładunkowa Street. All water cranes have been dismantled at the station. There are railway warehouses, currently occupied by wholesalers and shops. There were two wagon scales at the station; a 10-tonne one until 1975 and a 40-tonne one until 1988.

Next to the station, on the west side, there is a commemorative boulder with the inscription: “July 19, 1945. PKP. On the memorable anniversary of taking over the railway in the ancient Piast Land.”

LK No. 14 Łódź Kaliska – Forst/Baršć (353 km of line). LK No. 282 Miłkowice – Żary (102 km of line). LK No. 370 370 Zielona Góra Główna – Żary (53 km of line).

Currently, Żary station serves up to 1,000 passengers per day. On May 17, 2025, 33 trains departed from the station. You could go to the following stations: Forst Lausitz, Görlitz, Jelenia Góra, Legnica, Przemyśl Główny, Tuplice, Wrocław Główny, Zgorzelec, Zielona Góra Główna, Żagań. Carriers: PolRegio, Koleje Dolnośląskie. There is also one InterCity IC 76106 Mehoffer train on the Zielona Góra Główna – Przemyśl Główny route. The trains enjoyed good attendance, especially those to Legnica and Węgliniec.

Written by Karol Placha Hetman