Ostrołęka 2025-05-23

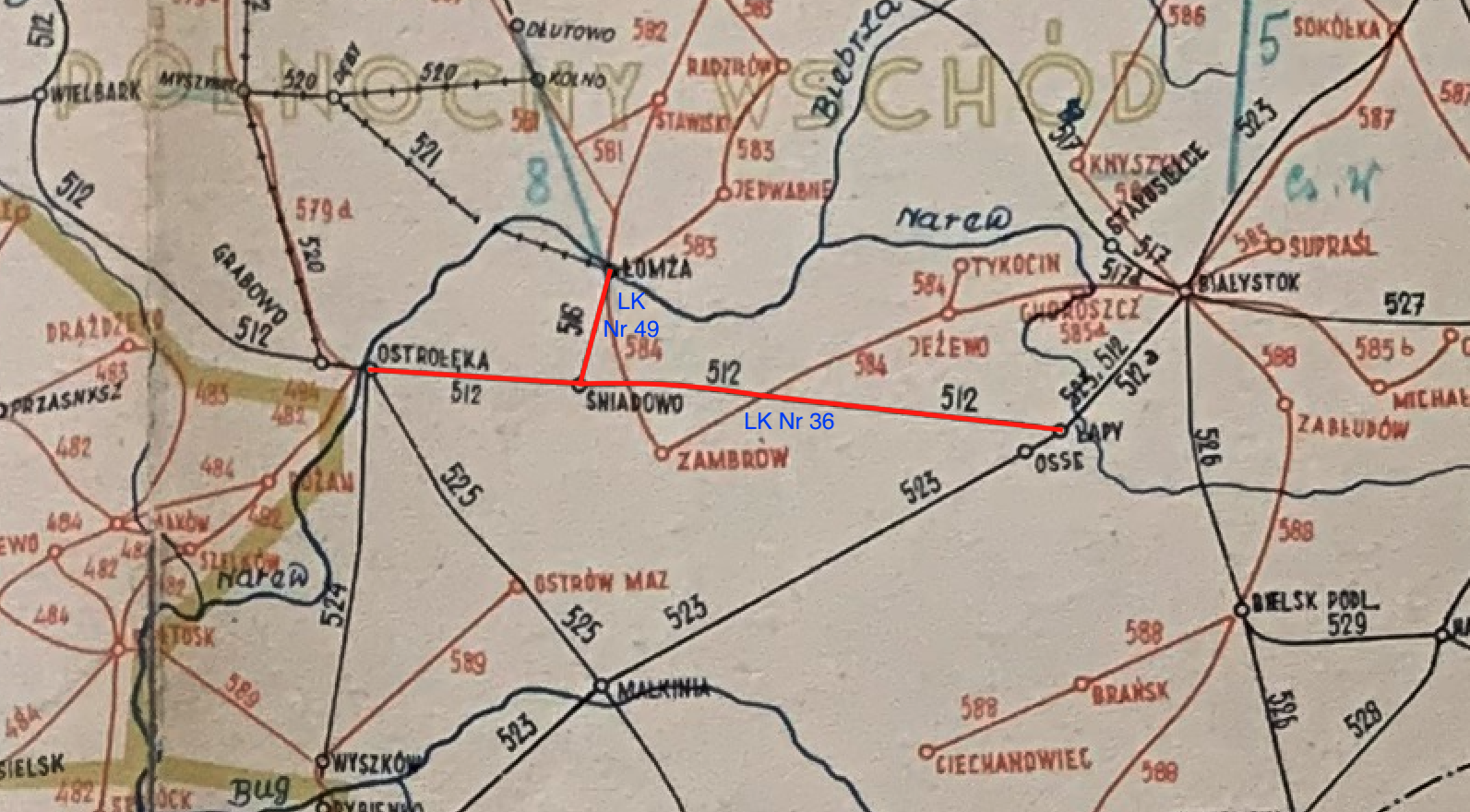

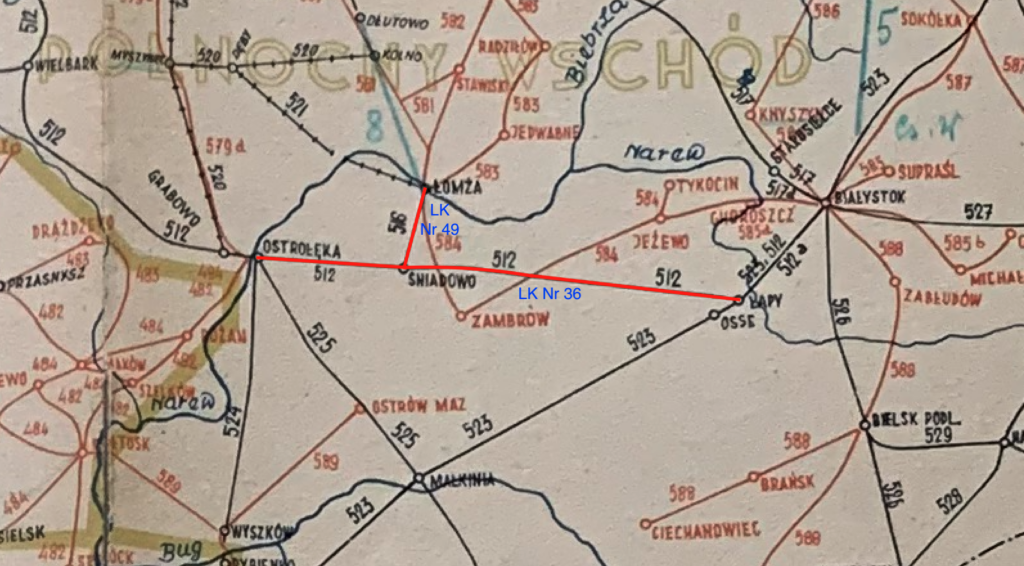

Railway Line No. 36 Ostrołęka – Łapy.

Railway Line No. 36 Ostrołęka – Łapy is a non-electrified, single-track railway line with a total length of 87.744 km. The line was opened on November 27, 1893. The line runs from Ostrołęka, through Śniadowo, Czerwony Bór, Czarnowo Undy, Kulesze Kościelne, Jamiołki, and Sokoły, to the Łapy station. At the Łapy station, the line joins LK No. 6 Warsaw – Białystok.

Podlaskie Voivodeship.

The Podlaskie Voivodeship is located in northeastern Poland, bordering Belarus and Lithuania. Białystok is the regional capital. Covering an area of 20,200 km², it is one of the largest voivodeships in Poland. With a population of only 1.15 million, it is the least populated voivodeship in Poland. Podlaskie Voivodeship is an exceptionally pristine region, with numerous national parks: Białowieża, Biebrza, Narwiański, and Wigry. This region of Poland is a mosaic of nations and religions. Poles, Belarusians, Lithuanians, and Tatars live here. Religious life here includes Catholics, Orthodox Christians, and Muslims. Tatar villages include Kruszyniany and Bohoniki, the only villages in Poland with wooden mosques. Descendants of Tatars brought here by King John III Sobieski in the 17th century live here. Agriculture, the food industry, and the timber industry dominate the region. Tourism, hunting, and fishing are also important to the region. This region is known for its beautiful landscapes, rich multicultural traditions, and peaceful pace of life.

The Białowieża Forest is the oldest natural forest in Europe, the last remaining primeval forest in the continent’s lowlands, and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The forest is protected and managed by local foresters. We demand that the European commune not lecture our foresters on how to care for nature. The mighty European bison is a symbol of the region. The Białowieża Forest is home to the largest wild population of these animals in Poland. The Biebrza Marshes are one of the largest and most important peat bogs in Europe. It is a bird paradise. Over 270 species of birds live here, including the white-tailed eagle and the aquatic warbler (Acrocephalus paludicola, a migratory bird not much larger than a thumb). The Augustów Canal is a 19th-century monument of Polish hydraulic engineering, connecting the Biebrza River with the Niemen River. The canal is over 100 km long and has numerous locks. It was here that Saint John Paul II used to visit. As a reminder, the Elbląg Canal is a Germanic monument of hydraulic engineering. Green Velo is Poland’s longest cycling trail, spanning over 2,000 km and passing through Podlasie, among other regions, showcasing the region’s most beautiful corners. The Podlasie region is famous for its embroidery. Koniaków lace and Podlasie embroidery are local handicrafts that have survived to this day. Podlasie honeys are protected by geographical indications. The region is also famous for its sękacz and kindziuk cakes.

Sękacz, also known as bankich, dziad, spit cake, or kołacz, is a traditional, labor-intensive cake from northeastern Poland, prized for its distinctive appearance resembling a cut tree trunk with “knots” visible in cross-section. It is baked from a sponge-fat mass that is gradually baked on a rotating spit, creating visible “rings” of the tree and “icicles” resembling the knots.

Kindziuk is a traditional Lithuanian cold cut known for its firmness and intense flavor. It is made from pork, which is salted, seasoned, and then placed in a pig’s stomach or bladder. After sealing, the meat is smoked and matured for a longer period, giving it a distinctive flavor and firm texture.

Podlasie was also a region of struggle against communism. The Augustów Roundup, a tragic event that took place in July 1945, is considered the largest post-war crime committed against Poles by Soviet forces and security services. The roundup lasted from July 12, 1945, to approximately July 28, 1945, immediately after the end of World War II. It was primarily carried out in the Augustów Forest, around Augustów, Suwałki, and Sejny, in the northern part of today’s Podlaskie Voivodeship. The aim of the roundup was to destroy the structures of the Polish independence underground, the Home Army, which had not submitted to the new communist government in Poland after the war. NKVD troops, in cooperation with the Security Service and the People’s Army, surrounded the entire region. Mass arrests were carried out. Approximately 7,000-10,000 people were detained. Most were released after interrogation, but approximately 600 people (mostly Home Army soldiers, but also civilians suspected of collaboration) disappeared without a trace. It is assumed that they were taken deep into the CCCP and murdered. Their burial sites remain unknown to this day. The Augustów raid is sometimes called “Little Katyn” because it was an operation aimed at the independence elite, and the truth about it was concealed for decades. Only after 1989 did historians begin to study and commemorate the subject. However, there are still political forces in Poland (Folk Germans, communists, Freemasons) who resent the remembrance of this tragedy.

The Białystok–Łomża–Ostrołęka railway line.

The Białystok–Łomża–Ostrołęka railway line was built during the partition period in Poland. This region belonged to the Kingdom of Poland, which was completely subordinated to the Muscovite state. The line was built solely for strategic purposes. The Muscovites wanted to create an efficient railway connection with the empire’s western border and draw closer to their Prussian brethren. The line to Ostrołęka, with a branch line to Łomża, was intended to enable the rapid transfer of troops and supplies from the interior of the empire to the Prussian and Austro-Hungarian borders if the Prussian brethren proved disloyal. The Narwin Railway was part of a broader system of the Vistula Railway and other lines running westward and southward. Economic development was secondary, and passenger traffic even tertiary.

The distinctive features of the Moscow railway lines in the Kingdom of Poland were: Their considerable distance from the most important cities. All lines were built with a 1524 mm gauge, which was intended to hinder potential enemy exploitation. The lines were laid out in straight sections, but consideration was given to whether expensive railway bridges would be necessary along this route. The lines were built as single-track to reduce costs.

Construction was primarily financed by the Muscovite state, as the line was of military and strategic importance. Costs were covered from the imperial budget and partially by issuing railway bonds. Private capital was involved to a lesser extent, but the Moscow military and tsarist authorities still had control and final decisions.

The Białystok–Łomża–Ostrołęka railway line was built in stages. Its starting point was at Łapy station, on the existing Warsaw–St. Petersburg Railway line (1862). Plans were drawn in Moscow after a prior site inspection by military engineers. Construction was commissioned to Moscow-based construction companies. A chief engineer was appointed, along with additional engineers: surveyors, geologists, hydrologists, and technicians. These were often brought in from deep within the empire due to a shortage of specialists. Workers were organized into artels, brigades with no fixed number of employees. Local workers from Podlasie and Mazovia were hired for manual labor, and for larger projects, seasonal workers from other parts of the empire were also hired. The workers lived in makeshift barracks, often without sanitary facilities. This led to widespread disease.

The land for the construction of the route was purchased from its owners, primarily from the Lithuanian nobility. But also from free peasants who owned fields along the planned route. The process was officially defined as expropriation for public purposes, meaning the state could seize the land but had to pay compensation. This process was handled by tsarist officials, mostly acting alone. There was considerable room for corruption, especially illiterate owners. Compensation payments were significantly underestimated, far below market value and often paid late. In theory, the compensation amount was determined by special commissions, which was a fiction. The least affected were the owners of estates and palaces. They often secured exclusive rights to supply food, beer, and alcohol to their workers. The worst-off were owners who refused to sell their land. In such cases, a tsarist employee would arrive with the tsarist police, and the owner would be imprisoned and exiled, while the land was seized by force. The decision was made by the tsarist authorities. Compensation was paid to the family anyway. These methods were employed because railway construction was considered a strategic investment, important for the state, especially from a military perspective. Therefore, the requirement was either buyout or forced expropriation with compensation. The scale of actual coercion depended on the region, local arrangements, and resistance from the owners.

Railway construction was carried out in stages: first, embankments and excavations, then bridges and culverts, and finally, tracks and station buildings. The vast majority of earthworks were done by hand: workers dug with shovels, removed earth with wheelbarrows and horse-drawn carts, and the embankments were built by piling up earth brought in by horse-drawn carts. Cartwrights, with their own carts and horses, earned the most. Narrow-gauge railway construction techniques were not used in the empire to transport building materials and ore (earth and rock). This was already being done in the West at that time. Steam engines were used primarily for specialized work, for example, for driving piles for bridges or powering pumps in flooded trenches. As soon as the first sections of track were laid, work wagons pulled by men or horses were used to transport earth and bring in materials. Stations were built according to a specific pattern, as were technical buildings. Red brick imported from the empire was used. Bricks from Polish brickyards were purchased only when there was a shortage of bricks from the Empire. But many structures were also built of wood. Steel rails and tar-impregnated sleepers were immediately installed along the route. Steel rails were several times more durable than iron rails.

Construction lasted from March to October. No work was done in winter, as such construction would have had disastrous consequences. Work lasted six days a week. Sundays were a day off. Those who were literate wrote letters to their families. Clothing was repaired and washed then. Workers worked from dawn, leaving their barracks for work before dawn. The day ended at sunset. Work continued even in the rain, often in mud. There was no occupational health and safety protection as we know it today: helmets, work clothes, work boots, or protective gloves. Pay was low. The workers were mostly local, but sometimes seasonal workers were brought in from further afield. There was a collective responsibility. If a worker in debt died, the entire artel would pay off the debt. There was a doctor who provided medications, which had to be paid for. If money was unavailable, the medications were supplied on credit. Workers were deducted from their wages for food.

The first steam locomotives used on this route were imported from Prussia and Austria. Later, domestically manufactured locomotives were introduced, modeled after Prussian locomotives. The first steam locomotives were built in the Moscow Empire, primarily at the Putilov Works in St. Petersburg (Putilovsky Plant) and the Bryansk Works (Bryanskiy Plant). All locomotives were classic tank locomotives or locomotives with a tender. Typical axle configurations were 1’C (or 2-6-0 in the Anglo-Saxon layout), sometimes 0-6-0 for lighter freight trains. The locomotives burned hard coal and drew water from small water towers at stations. On such local strategic-utility lines, several locomotives (4-8) were typically stationed in a depot to service the entire route. Half of the locomotives were light, the other half heavy. There was no division into military and civilian trains. The entire railway was militarized. A typical train consisted of a locomotive, 3-5 passenger cars, and 8-12 freight cars. The freight cars had a load capacity of up to 10,000 kg. The military also had its own cars, such as flatcars for transporting military equipment, tank cars, and armored trains.

In 1900, four pairs of passenger trains ran on the route. The schedule was arranged so that the first morning train went to Białystok, and the last evening train to Ostrołęka. Freight trains ran irregularly, with 5-15 per day. As you can see, traffic was not heavy. Traffic organization was modeled on Western systems. Each train had a timetable and detailed instructions regarding travel times between stations and checkpoints. The timetable was a fundamental document, and strict adherence to it was crucial. A line blocking system was used on sections of the line, prohibiting the entry of the next train until the previous one had cleared the given section of track. Initially, there were no entry or exit signals on the line. Trains were dispatched by stationmasters or signalmen. Stations such as Ostrołęka, Śniadowo, Łapy, and Białystok housed signalmen (signalmen). Signalmen operated the switches, acting on the orders of the stationmaster or signalman. Each station had clocks synchronized to the local time in the region. Communication between stations and checkpoints was via telegraph or wire telephones.

During the Great War, the Germans regauged the track from 1524 mm to 1435 mm. At that time, shaped semaphores were installed, which significantly improved rail traffic. Many turnouts were converted to turnouts controlled from the station by means of a power transmission. Additional water towers and coal entanglements were built.

During World War II, the line provided an alternative east-west connection. Here, the Germans did not invest significantly.

Between 1983 and 1985, the railway track was renovated on the Śniadowo-Łapy section. Since then, the track has consisted of a jointless track (S49 rails, K-type fastening, and pre-stressed concrete sleepers).

On April 3, 2000, passenger train traffic on the Śniadowo-Łapy section was suspended, followed a month later by freight train traffic. From 2000 to 2017, rail traffic operated only on the Ostrołęka–Śniadowo section. Prefabet products were transported. Occasional service was also provided on other sections of the route. Special trips were also organized on LK No. 36. For example, on October 20, 2013, a special train ran on the Łapy–Łomża–Łapy route to celebrate the 120th anniversary of the Narew Railway. Passenger traffic returned with great difficulty and delay. In 2014, Koleje Mazowieckie launched its first irregular services using VT628 diesel-electric DMUs.

In 2015, the new United Right government invested PLN 30 million in the revitalization of LK No. 36. A year earlier (2014), the Marshal of the Podlaskie Voivodeship allocated funds for the implementation of the line’s revitalization plan. The work lasted from March 2017 to July 2018. On April 5, 2018, freight services were resumed on the Śniadowo-Łapy section. At the same time, the Ostrołęka-Śniadowo section was closed for renovation. The entire line was opened to carriers on July 30, 2018. In November 2018, echelons re-entered the line, covering the route to Czerwony Bór. Since 2019, freight traffic has steadily increased on the route. On the Ostrołęka-Śniadowo section, there were 4-5 trains per day, and on the Śniadowo-Łapy section, 1-2 freight trains. On October 6, 2020, the Sokoły siding reopened. As of March 18, 2024, passenger trains have been running on the entire line. On July 22, 2025, the Białystok – Ostrołęka route was served by two pairs of passenger trains of the PolRegio carrier, in the morning and in the afternoon.

Currently (2025), the maximum speed on Railway Line No. 36 is 120 km/h. All stations on the route had shape signals installed during the Great War. In 2017, shape signals were replaced with light signals.

Plans to electrify Railway Line No. 36 and Railway Line No. 49 are still in effect. For the time being, they are not economically necessary.

The largest steel bridge on Railway Line No. 36 is over the Gać River. It covers 42.732 km of line. For a long time, it was a wooden and steel bridge. The current bridge was built in 1958. The last renovation was completed in 2018. The bridge is a three-span, steel, plate girder bridge.

Route of Railway Line No. 36 Ostrołęka – Łapy.

Ostrołęka Station (0.00 km, elevation 106 m) This is practically the village of Kaczyny Stara Wieś. It is a junction station, where lines No. 29, 34, 35, and 900 are located. After the station, the line crosses Juliusza Słowackiego Street, DW No. 627. Then there is an intersection at Krucza Street. On the northern side of the line is the ISE Małkinia Road Base. Further on, there is an intersection at Mazowiecka Street. Then there are four more intersections on local roads.

Kurpie passenger stop and a former loading bay (9.45 km, elevation 110 m). Nearby, on the southern side, is a roof tile factory. Further on, the line crosses three more local roads. There is a single-span, plate girder railway bridge over the Ruż River. Further on, there are three intersections with local roads. The line passes through farmland and small forests. Żyźniewo passenger stop (18.55 km, elevation 113 m). Passenger trains stop here occasionally.

20.94 km is the border of the Masovian and Podlaskie Voivodeships. The line then passes beneath the S61 highway and the Via Baltic. Next, there’s an intersection with a local road.

Śniadowo station (25.52 km, elevation 132 m). Previously, the station was moved 2 km to the east. Lines No. 49, 36a, and 36b are located here. It passes through the station at the intersection of DW No. 677. Several workplaces are located near the station, the largest being Prefabet Śniadowo, which has its own siding. Ratowo is a branch station for line No. 36a. Further on, the line enters the forest.

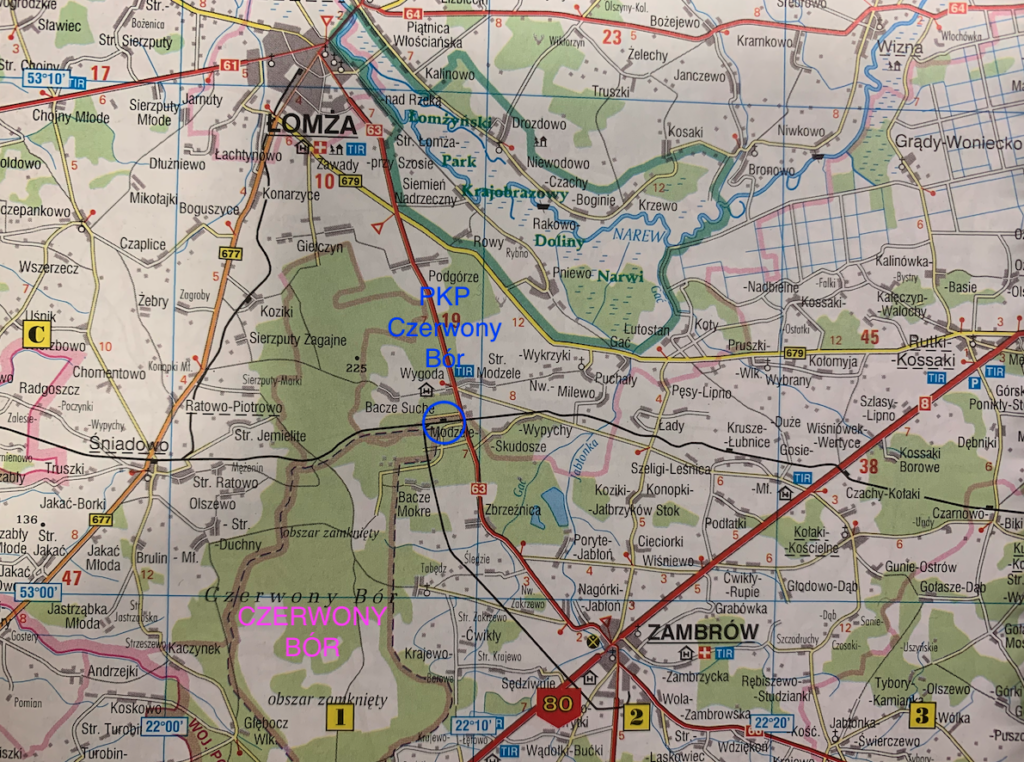

Czerwony Bór: passenger stop, military station (36.36 km, elevation 136 m). Railway line No. 50 to Zambrów is located here. Czerwony Bór is a training ground and a prison. After the station, the line crosses national road no. 63.

Borowe was the access point (41.65 km, elevation 109 m). Once again, there are farmland areas. Further on, the line crosses local roads three times at intersections. There is a railway bridge over the Gać River.

Łubnica Łomżyńska passenger stop (47.43 km, elevation 131 m).

Kołaki (Kołaki Kościelne) passenger stop (51.97 km, elevation 144 m). The line re-enters the forest and passes two local roads.

Czarnowo Undy (Czarnowo Biki) station (57.95 km, elevation 163 m). There are three through tracks here. Near the station, on the north side, is a furniture manufacturer. The line crosses the Rokitnica River.

Kulesze Kościelne passenger stop (62.62 km, elevation 144 m). There’s an intersection in front of the stop, Kolejowa Street.

Wnory (Nory Pażochy) passenger stop (km 68.48, elevation 151 m).

Jamiołki passenger stop (km 71.50, elevation 146 m). After the stop, there’s an intersection with a local road. The line passes the Ślina River. Further on, there’s an intersection with national road no. 671.

Sokoły passenger stop and loading bay (km 76.61, elevation 135 m). Sokoły is a village with 1,518 inhabitants (2011). It boasts the beautiful Basilica of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The settlement was founded in the 14th century. After the station, the line passes the intersection of Kolejowa Street and then national road no. 678.

Roszki Leśne passenger stop (km 79.24, elevation 124 m).

Płonka Kościelna passenger stop (km 83.17, elevation 131 m). The line passes an intersection with several local roads. This is the outskirts of Łapy. There is an intersection at Warszawska Street, and the line passes under the viaduct of the National Railway No. 681, Brańska Street. From the south, there is the double-track, electrified railway line No. 6.

Łapy station (88.16 km, elevation 122 m). Railway line No. 6 is located here.

Railway line No. 49 Śniadowo – Łomża.

The Śniadowo – Łomża railway line No. 49 is 17.261 km long. The line is single-track, non-electrified, and was built from the outset to a 1435 mm gauge. The line was built during the Great War in 1915. Passenger trains operated on the line until May 22, 1993. Passengers had access to replacement bus services until April 2000. Lack of repairs resulted in freight trains being limited to a speed of 20 km/h. Freight traffic was suspended in 2001. Only occasional trains appeared on the route. Thanks to the Marshal of the Podlaskie Voivodeship and a financial subsidy, freight traffic resumed in 2015. One or two freight trains passed through the route daily. In 2023, the Podlaskie Voivodeship government and PKP PLK signed an agreement to revitalize the line. Bids for the tender were opened in November 2024.

The track layout allowed access to the line from both Śniadowo (from the west) and Łapy station (from the east). As a result of the renovation, the entrance (switchboard on the eastern side) was removed. As a result of the renovation, the maximum train speed is 80 km/h.

Line No. 49 Śniadowo – Łomża begins at Śniadowo station. The track runs west and curves left toward the north. The line is constantly accompanied by National Road No. 677 (on the west) and the S61 Via Baltica motorway (on the west, behind National Road No. 677). The railway line runs through farmland and meadows. The line passes the towns of Ratowo Piotrowo, Konopki Młode, Sierzputy Zagajne, and Koziki. It then passes under the new National Road No. 63 viaduct (due in 2025). Next comes an intersection, National Road No. 677. On the west side is the village of Konarzyce. Beyond that is an intersection, Łomżyńska Street. This is the beginning of the suburb of Łomża. There are intersections of Pawia, Strusia, Poznańska (industrial area), Rotmistrza Witolda Pilecki, and Aleja Marszałka Józefa Piłsudskiego. The station in Łomża is a major landmark.

The first station in Łomża was wooden. The second station was large, brick, and two-story. It was destroyed in 1939 by the Germans. In front of the station was a triangle for turning locomotives. During the communist era, the station had one platform and one platform edge. It houses a signal box for “Łm,” a dispatcher’s building (later a fuel depot office, closed in 2024), a wagon scale, a storage yard, a coal yard, and semaphores (departure and arrival) and lights (at the end of the track). There is no station building. A bus station is located on the eastern side.

But Łomża also had a narrow-gauge railway, which opened on January 1, 1922. The rail gauge is 600 mm. The former narrow-gauge railway station was adjacent to the standard-gauge station. The station building, built in 1929, remains unaltered, with some of the premises used by PKP Cargo SA. The building is located at 172B Sikorskiego Street (Kolejowa Street). The station housed the following buildings: a station house, a locomotive shed, a freight forwarding facility, a ramp and storage yard, a warehouse, and an outbuilding.

The narrow-gauge line ran westward from Łomża to Dęby station. The line was 49 km long and connected with the further narrow-gauge railway network and stations: Myszyniec, Kolno, Grabowo, and Pudy. On the Dęby-Łomża section, the line crossed the Narew River on a wooden bridge; on the Morgowniki-Nowogród section, the line was closed in 1973.

Written by Karol Placha Hetman